My father was married to his job. We would see him, but not that much. He left the house at 6:15 am or thereabouts and returned home about 5:45 most nights. He didn’t have a lot of energy for anyone at that point. I know we had dinner together, but I don’t recall him bringing a whole lot of enthusiasm to that. He was married to my mother, and they were almost like one organi

My father was married to his job. We would see him, but not that much. He left the house at 6:15 am or thereabouts and returned home about 5:45 most nights. He didn’t have a lot of energy for anyone at that point. I know we had dinner together, but I don’t recall him bringing a whole lot of enthusiasm to that. He was married to my mother, and they were almost like one organi

My father was married to his job. We would see him, but not that much. He left the house at 6:15 am or thereabouts and returned home about 5:45 most nights. He didn’t have a lot of energy for anyone at that point. I know we had dinner together, but I don’t recall him bringing a whole lot of enthusiasm to that. He was married to my mother, and they were almost like one organism in activities, but I suspected much of his best energy went into his job. Well, I more than suspected. I had evidence.

Every once in a while, I got to go to school with my Dad. He was always a teacher, but towards the end of his 32-year stint in teaching he was also the head of the English Department as well as the Vice Principal of Martin Luther King Jr. High School. We’d walk into the school and he would be barraged with students and staff, “Mr. Blaine!” People had questions for him, smiles, complaints. He wore a suit and was buttoned in and down. He could field it all. He’d turn to me and take me upstairs. I was there less to spend time with him, and more so he could put me to work in the stacks.

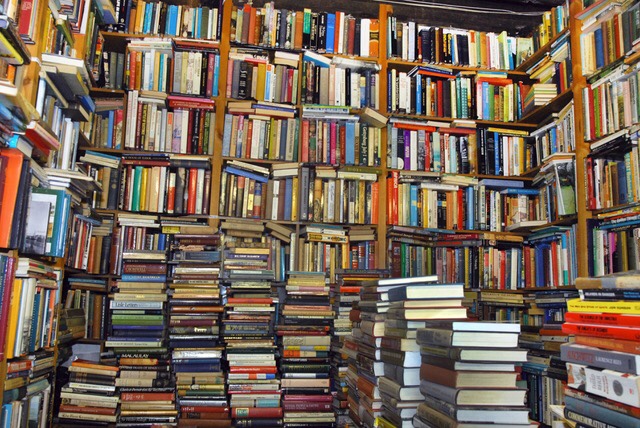

There were these industrial shelves filled with multiple copies of books: To Kill A Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, Go Tell It On The Mountain, all the classics and mandatory reading for high school English. They stretched to fill the 20×30 windowless room. I’d flip open the book and scan the tenant’s names. Often the names would slip outside the designated lines, the last name teetering on the book log precipice. I couldn’t tell whether my father had taught that particular child, but I imagined if they had been in his class and written so disrespectfully it wouldn’t have gone particularly well.

I loved gathering the books, putting them in order, taking the neglected books and reinforcing a cover, weighing whether the book could take another season of battering. My father was there to teach the kids. He was there to oversee the other teachers. My father. My father loved these books, so I loved these books. I couldn’t help it. And I loved fantasizing about how each of these books traveled with its temporary owner for months. Making a path to their home and back. Touching the tar on the basketball court, withstanding the subway floor, swallowed in an asphyxiating book bag, barely seeing the light of day. And then every summer, these books were officially on vacation, enjoying the view from the one side exposed townhouse apartment of this industrial shelving in the English department book storage. Except for the one or three books still playing hooky somewhere — under a bed – forgotten – unwanted – or stealing away time at the side of a public pool.

I loved it in the stacks. The smell of paper was flavorless but sturdy. The smell of long-lasting curriculum. The smell of what my Dad believed was worth the children’s time.

sm in activities, but I suspected much of his best energy went into his job. Well I more than suspected. I had evidence.

Every once in awhile I got to go to school with my Dad. He was always a teacher, but towards the end of his 32 year stint in teaching he was also the head of the English Department as well as the Vice Principal of Martin Luther King Jr. High School. We’d walk into the school and he would be baraged with students and staff, “Mr. Blaine!” People had questions for him, smiles, complaints. He wore a suit and was buttoned in and down. He could field it all. He’d turn to me and deliver me upstairs.I was there less to spend time with him, and more so he could put me to work in the stacks.

There were these industrial shelves filled with multiple copies of books: To Kill A Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, Go Tell It On The Mountain, all the classics and mandatory reading for high school English. They stretched to fill the 20×30 windowless room. I’d flip open the book and scan the tenant’s names. Often the names would slip outside the designated lines, the last name teetering on the book log precipice. I couldn’t tell whether my father had taught that particular child, but I imagined if they had been in his class and written so disrespectfully it wouldn’t have gone particularly well.

I loved gathering the books, putting them in order, taking the neglected books and reinforcing a cover, weighing whether the book could take another season of battering. My father was there to teach the kids. He was there to oversee the other teachers. My father. My father loved these books, so I loved these books. I couldn’t help it. And I loved fantasizing about how each of these books traveled with its temporary owner for months. Making a path to their home and back. Touching the tar on the basketball court, withstanding the subway floor, swallowed in an asphyxiating book bag, barely seeing the light of day. And then every summer, these books were officially on vacation, enjoying the view from the one side exposed townhouse apartment of this industrial shelving in the English department book storage. Except for the one or three books still playing hooky somewhere — under a bed – forgotten – unwanted – or stealing away time at the side of a public pool.

I loved it in the stacks. The smell of paper was flavorless but sturdy. The smell of long lasting curriculum. The smell of what my Dad believed was worth children’s time.

Read full article

Read full article