I always knew the story. I had heard it a fair amount. It was one of those things I heard as a fact, sometimes as the backdrop for why my father’s family suffered misfortune, other times just as a peg in the chronology of my father’s childhood.

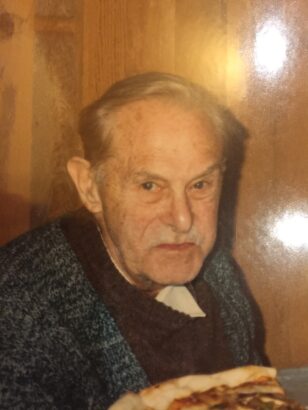

My paternal grandfather accepted a job on the Brooklyn docks as a guard of sorts. It was the time of the Great Depression. Jobs were scarce. This was a great job — a boon. And he blew it. Because on his very first day my grandfather accepted a bribe to look the other way while some guys smuggled in some goods, which may have been black market items, but regardless not paying the tax was illegal, so my grandfather lost this coveted job. The fallout was intense. He could not find a job for weeks, or was it months? The main image I carry from this period is that my father, who was an adolescent at the time, sat in the basement sewing burlap sacks and bringing them to the local store and getting a nickel a bag. That nickel meant a lot. It paid for the family’s food at times. They never starved but they were all hungry. Hungry to eject themselves past this horrible stain, which my grandfather never forgave himself for doing.

This story weaved its way through me. I marinated on this story. I focused on the image of my father sewing burlap sacks. In my story he sewed them by candlelight, having lost the electricity to illuminate the house. I added this as an embellishment to accentuate the pain of the whole scenario. Otherwise, I buried this story until it surfaced in a rather unexpected way.

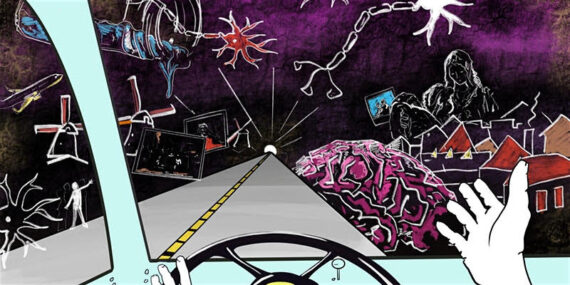

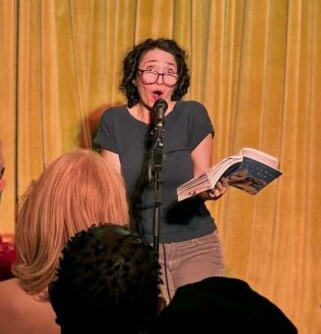

I was going through a period of commuting to libraries to perform an original kids show in somewhat remote suburbs of Philadelphia. This was before GPS and I would print out my MapQuest directions of the destination, estimate how long it might take me, head out, and proceed to get lost. You may think it’s not possible to get lost if you have directions, and it’s the middle of the day and there’s enough light to read the paper. But I was great at this. Time would get closer and closer to show time. I would panic, then I’d make more mistakes. Oh no, oh no! I am lost. I don’t have the number for the venue. Oh no, oh no! In my family on time is 10 minutes early, so being late was sacrilegious for me.

After a particularly bad incident of a super late arrival for one of these performances, I made my way back home, without even looking at the directions, then sat in my coaching office and cried and faced into the awful feelings in my gut. I realized I was sabotaging myself. The show was adorable, sweet, fabulous. The only way I could mess up was being late, so I kept being late. Why would I keep doing that to myself?! I sat and breathed and listened. I really wanted to know. And what came up was that I had to mess up like my grandfather did. I was trying to replicate his shame. I was successful in replicating his shame. I was able to imagine his shame, because by doing this I had my own. I kept welcoming the waves of sadness and despair and loss. I cried for my grandfather and the forgiveness he withheld from himself his whole life. He became a lawyer but never let himself practice law. His shame was so deep he couldn’t let himself be really seen. He needed to hide. I imagined him next to me, us holding hands. My gruffest grandfather, I recalled how his blue eyes softened when we’d hold hands his last year of life when he headed into his 92nd year. I cried and told him how sorry I was that he had never forgiven himself, but it was time to accept the shame and move through it. I told him I needed to feel it now so I could move through it. I told him I was sorry he had not had the chance to do it, but I would do it now, for both of us. I felt a weight lift from my whole being.

I forget that this story can be useful to others. It was so monumental for me. It was completely transformational for me. I was never late to a gig again. I ended that pattern. I shared this story with a client recently, indicating that sometimes a pattern which restricts us may originate in our families before we even existed. The following session the client fixed his eyes on me, and he said, “I feel so differently about you ever since you shared that story. I think you can hear my shame. I trust you to help me through it now.” He is indeed moving through it, even laughing about some old patterns which caused him to lose his ideal job a decade ago. But he is now letting himself move forward again. As we all must.

I really enjoyed reading a new book by Gay Hendricks over the winter break. (I got my coaching certification from The Hendricks Institute which he created with his luminous wife Kathlyn Hendricks.) In “The Joy of Genius” Gay talks about the value and importance of recognizing there are many things we don’t have control over and some things we do. Yes, you may also recognize this as the serenity prayer, and I wrote about the concept in an earlier blog post as one of the main teachings of the philosopher and once-slave Epictetus. I’ve encountered some people that say we don’t have control and it’s best to let go regarding just about everything. I find that very hard and sometimes a very boring attitude to have about life. I like trying to go for things, even if they seem unlikely. Where does that leave me?

I really enjoyed reading a new book by Gay Hendricks over the winter break. (I got my coaching certification from The Hendricks Institute which he created with his luminous wife Kathlyn Hendricks.) In “The Joy of Genius” Gay talks about the value and importance of recognizing there are many things we don’t have control over and some things we do. Yes, you may also recognize this as the serenity prayer, and I wrote about the concept in an earlier blog post as one of the main teachings of the philosopher and once-slave Epictetus. I’ve encountered some people that say we don’t have control and it’s best to let go regarding just about everything. I find that very hard and sometimes a very boring attitude to have about life. I like trying to go for things, even if they seem unlikely. Where does that leave me?

Read full article

Read full article